Ceramic injection molding represents one of those quiet industrial innovations that, whilst unknown to most people, has fundamentally altered what humans can manufacture and how we live. It is a process that takes materials older than civilization itself and subjects them to techniques borrowed from the plastics industry, producing components so precise they can function inside the human body for decades or withstand temperatures that would vaporize steel. The transformation from ancient craft to modern precision manufacturing tells us something about humanity’s persistent drive to bend the physical world to our purposes, regardless of how resistant that world might be.

When Ancient Materials Meet Modern Methods

Ceramics have accompanied human civilization for millennia. Clay pots, fired bricks, and porcelain vessels represent some of our earliest technological achievements. Yet traditional ceramic manufacturing remained fundamentally limited. A potter’s wheel can produce beautiful vessels, but it cannot create the intricate geometries required for a hip replacement or a turbine blade. For most of history, this presented no particular problem. Today, it presents an obstacle that ceramic injection molding elegantly circumvents.

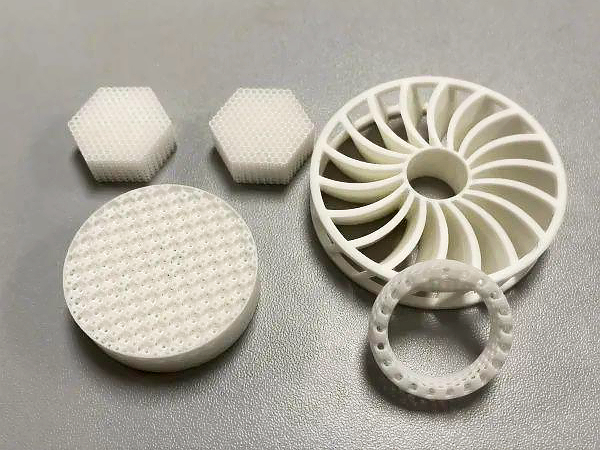

The process works by temporarily making ceramics behave like something they are not. Ceramic powders, ground to particles measuring mere micrometres, are mixed with organic binders that melt when heated. This mixture flows through injection molding machinery like conventional plastics, filling complex mould cavities under high pressure. Once cooled and ejected from the mould, the parts undergo a transformation in reverse: the binders are carefully removed, and the ceramic particles are fused together through sintering at temperatures approaching 2,000 degrees Celsius.

What emerges is pure ceramic, shaped with precision impossible through traditional methods. The irony is palpable: to make ceramics more versatile, we must first make them temporarily less ceramic.

The Technical Choreography

Ceramic injection molding unfolds through a carefully orchestrated sequence, each step demanding exacting control:

- Mixing ceramic powders with thermoplastic binders at ratios typically between 50 and 65 percent ceramic by volume

- Heating the mixture until it achieves fluid consistency suitable for injection

- Forcing the material into precision moulds under pressures that can exceed 1,500 bar

- Cooling the molded parts until the binder solidifies, trapping ceramic particles in their designed configuration

- Removing binders through thermal decomposition or chemical dissolution over hours or days

- Sintering at extreme temperatures to fuse ceramic particles into solid, dense components

The process sounds straightforward in description but proves demanding in execution. Parts shrink 15 to 20 percent during sintering as particles fuse and voids disappear. Predicting and compensating for this shrinkage requires sophisticated modelling. A component designed to measure precisely 10 millimetres after sintering must be molded at approximately 12 millimetres, with the exact ratio depending on ceramic type, particle size, and sintering conditions.

Applications Spanning Industries

Walk through a modern hospital and you encounter ceramic injection molding products at every turn, though you would never know it. Zirconia dental crowns restore damaged teeth with materials that match bone’s mechanical properties. Hip joint components constructed from alumina ceramics articulate smoothly for decades inside patients. Surgical instruments incorporate ceramic cutting edges that maintain sharpness through countless procedures whilst remaining chemically inert.

Singapore has developed particular expertise in medical applications of ceramic injection molding. “Singapore’s ceramic injection molding sector supports the nation’s medical technology industry,” according to industry analyses, “producing biocompatible components for implants and surgical devices under clean room conditions meeting international medical device standards.”

The electronics industry relies equally heavily on ceramic injection molding:

- Insulating components protecting circuits from electromagnetic interference and thermal stress

- Substrates supporting microelectronic assemblies in smartphones and computers

- Sensor housings maintaining functionality in extreme environments

- Connectors ensuring signal integrity in telecommunications infrastructure

Aerospace applications exploit ceramic’s unique combination of properties. Turbine components fashioned through ceramic injection molding withstand combustion temperatures where metals would soften and fail. Sensor housings survive vibration, thermal cycling, and corrosive environments. The same material properties that made ceramics useful for ancient cooking vessels make them indispensable for modern jet engines.

The Economic Reality

Yet Ceramic injection molding remains economically viable only under specific conditions. Tooling costs for precision moulds typically range from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars. These investments make sense only when distributed across large production volumes. A manufacturer producing 50,000 identical components annually can justify the tooling expense. A craftsperson needing 50 custom pieces cannot.

This economic reality shapes which products benefit from ceramic injection molding. Mass-produced medical implants, electronics components manufactured by the million, and automotive sensors produced at scale all prove suitable. Custom architectural elements, artistic ceramics, and low-volume industrial parts typically cannot bear the tooling costs.

Quality Challenges and Defect Investigation

When ceramic injection molding fails, the consequences can prove catastrophic. A defective hip implant might fracture inside a patient years after surgery. A cracked turbine component could trigger engine failure. Consequently, quality control in ceramic injection molding has evolved into an exacting discipline.

Common defects include debinding cracks caused by removing binders too rapidly, sintering distortions from uneven heating, and residual porosity from inadequate densification. Non-destructive testing methods probe for internal flaws. Dimensional inspection verifies uniform shrinkage. Mechanical testing confirms strength properties.

Looking Forward

As we confront challenges from ageing populations requiring more joint replacements to aerospace systems demanding ever-higher performance, ceramic injection molding will likely expand its reach. New ceramic formulations promise improved properties. Advanced process controls reduce defects. Computer modelling accelerates product development.

The process reminds us that human ingenuity often succeeds by working with materials rather than against them, finding ways to coax desired behaviors from substances that initially seem intractable. From ancient pottery to modern precision manufacturing, ceramics have accompanied our technological journey. Ceramic injection molding simply represents the latest chapter in this long collaboration between humans and the materials we have learned to shape.